Blaming other people for the bad stuff in your life usually doesn’t happen out of nowhere.

In fact, it’s often the product of early survival instincts. Many adults who deflect blame learned young that taking full responsibility wasn’t safe, valued, or even an option. When you grow up having to protect yourself from shame, fear, or punishment, blame-shifting can become a reflex. Here are some early experiences that often shape that pattern—and why understanding it matters more than judging it.

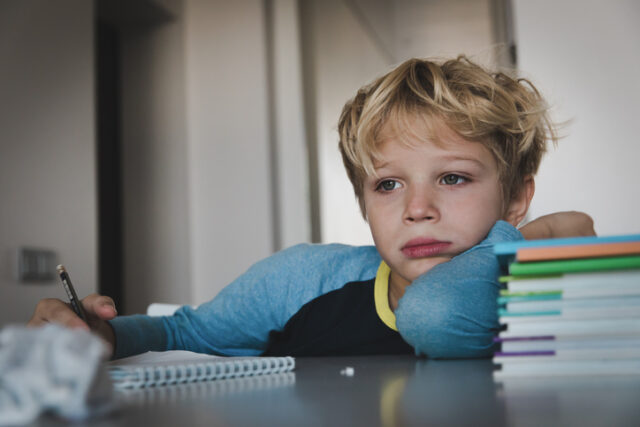

1. They were harshly punished for small mistakes.

If even tiny missteps led to big consequences—yelling, shaming, harsh punishments—it makes sense that a child would learn to distance themselves from anything that looked like “fault.” Mistakes didn’t feel like part of growing. It felt like proof you were bad or unworthy. As adults, that ingrained fear doesn’t just vanish. They might feel a deep, almost automatic panic at the idea of being wrong, and blame everyone else as a way to dodge that deep, old fear of being punished all over again.

2. They watched adults avoid accountability constantly.

Kids absorb what they see long before they process what they hear. If their parents constantly blamed bosses, friends, or even the kids themselves for every bad outcome, they internalised that dodging accountability was normal. When they grow up, blaming other people often doesn’t feel like manipulation; it feels like the only way to operate. It’s a learned survival strategy, not always a conscious choice to hurt anyone.

3. They were made to feel responsible for adult problems.

Being blamed for a parent’s bad mood, finances, or relationship troubles teaches a child one damaging lesson: you’re the problem. To cope, many kids start pushing blame away instinctively, even before they understand what blame really is. Later, as adults, the idea of absorbing even fair blame can feel intolerable. They’ve already carried unfair loads for too long, and their system rejects more blame before it even sticks.

4. They were praised only when they were perfect.

In some homes, love and approval were conditional on performing flawlessly. Being human—messy, wrong, or learning—wasn’t acceptable. You had to hide mistakes or risk losing affection, respect, or even basic kindness. That kind of environment wires people to associate being wrong with danger. Blaming other people becomes a defence mechanism because admitting to flaws feels tied to survival, not just pride.

5. They lived under “no excuses” expectations with zero compassion.

Growing up in a home that demanded perfection without allowing for humanity hardens people in strange ways. Mistakes weren’t moments for teaching; they were opportunities for punishment, shame, or withdrawal of love. Later in life, the emotional cost of owning mistakes can feel unbearable. So they learn to deflect quickly and fiercely because that’s what once kept them safe—emotionally, and sometimes even physically.

6. They were constantly compared to “better” siblings or peers.

Constant comparison damages a child’s sense of inherent worth. If you’re always less-than someone else, your self-esteem becomes brittle, and owning mistakes feels like handing people more ammunition to tear you down. As adults, blaming everyone else becomes less about arrogance and more about self-protection. It’s easier to point the finger outward than admit anything that might invite more judgement or shame.

7. They had caregivers who blamed them unfairly.

Sometimes kids get scapegoated in families, taking the fall for things that had nothing to do with them, just because it’s easier for an adult to blame a child than deal with their own failings. Children raised in that kind of dysfunction often internalise that blame is dangerous, random, and humiliating. As adults, they fight to avoid it instinctively, even when taking responsibility would actually serve them better.

8. They grew up feeling invisible and unheard.

Being emotionally neglected doesn’t just create loneliness; it creates a quiet desperation to be seen and validated. Sometimes blaming other people becomes a subconscious way to reclaim power or force attention when silence didn’t work. It’s not about being manipulative. It’s about needing someone, anyone, to notice you existed, had feelings, and were impacted too. In adulthood, that reflex can persist long after the original hurt has faded.

9. They lived in constant conflict environments.

When chaos was the norm—screaming matches, emotional outbursts, emotional whiplash—children learned quickly that being blamed could mean being targeted. Blame wasn’t just unpleasant; it could be dangerous. In those homes, survival sometimes meant making sure someone else took the fall first. As adults, the habit to shove blame outward still feels like survival, even when the stakes are no longer life-altering.

10. They were never taught how to manage guilt or shame.

Learning how to feel bad without collapsing into despair is a skill, not an instinct. Without guidance on how to sit with hard emotions safely, guilt and shame feel overwhelming—too big to handle. Blame becomes a shortcut: push it away fast, so you don’t get swallowed. If you never learned how to hold your mistakes with compassion, avoiding them becomes a reflex just to stay afloat.

11. They were regularly gaslit about their experiences.

When your reality is constantly denied—“You’re overreacting,” “That’s not what happened”—you lose trust in your own perspective. Responsibility becomes a confusing minefield where you’re never sure what’s true. Adults who were gaslit often struggle deeply with accountability, not because they’re dishonest, but because their internal compass was scrambled long ago. Blaming anyone and everyone else feels like a way to regain ground in an emotional landscape that once betrayed them.

12. They were shamed for normal emotional reactions.

If being sad, angry, frustrated, or even joyful got you mocked or punished, you learned early to bury your real feelings deep. Expressing emotion meant inviting harm. Blaming other people later in life isn’t about refusing to take responsibility—it’s about staying emotionally armoured. Admitting fault means opening up feelings that were once punished, and that takes more courage than most people realise.

13. They had parents who couldn’t tolerate weakness in themselves.

If your parents refused to admit mistakes, feared vulnerability, and punished anything that looked like weakness, you absorbed the same rules. Admitting fault didn’t just mean being wrong—it meant being exposed, unsafe, unacceptable. In adulthood, passing the blame feels like basic protection. Vulnerability was trained out of you early, and building it back later takes patience, self-compassion, and sometimes a whole lot of unlearning.

14. They grew up equating mistakes with losing love.

At the deepest level, people who deflect blame often aren’t trying to avoid consequences—they’re trying to avoid abandonment. If love and approval were only given when you were “good,” mistakes became emotionally catastrophic. As grown-ups, even small admissions of fault can trigger old survival fears. Blaming other people isn’t about avoiding accountability—it’s about avoiding the deep, ancient terror of being unloved for being imperfect.